My father-in-law was a hobby photographer. He loved the technical details of determining aperture, shutter speed and ISO, tracking each shot’s specifications for future reference. He took deep vistas of natural wonders and close-up studies of people, especially his wife and children.

More importantly, he inspired others to be photographers. His younger brothers loved photography as much as he did and tried to out-shoot each other. His wife took up the challenge of matching his skills and continued that calling long after he he had gotten bored with point-and-shoot technology. His older son borrowed the camera frequently until he received his own. As a result, hundreds of images in digital, slides, negatives and prints existed to help tell his life story.

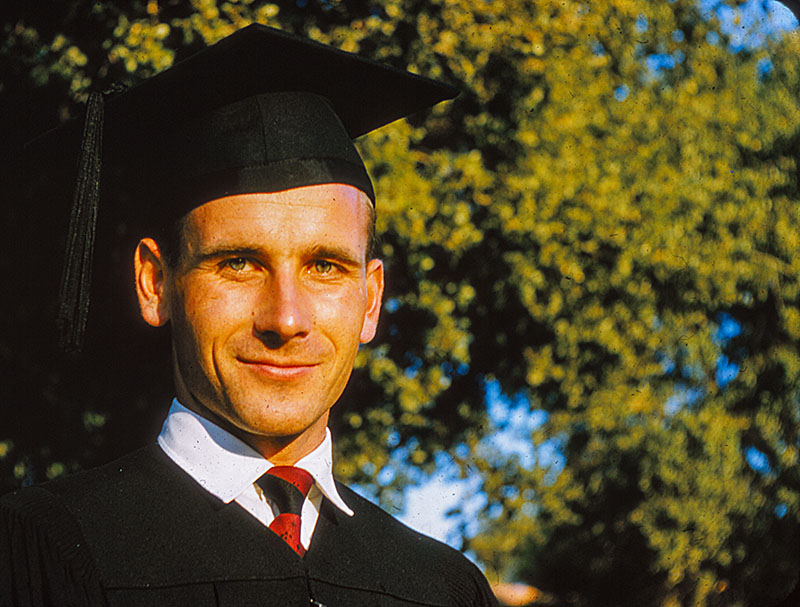

My father-in-law, two years after coming to the United States, graduating from Stanford University. Photo taken by one of his younger brothers. Slide scanned and color corrected by JJS

It’s because of those *other* photographers that we have a clear record of him. He didn’t bother with self-portraits. Through his life, those who *loved* him caught him again and again doing the things he loved.

- His intense stare as he studied a plant or a rock.

- His loving smile with a cat who decided this man meant ‘home.’

- His proud toiling in his yard, either weeding, watering, raking, planting, picking fruit, or splitting wood.

- His analyzing of jigsaw pieces for a puzzle.

- His mischievous twinkle as he blocked someone else in a tabletop game.

Photos are unique. That particular moment of time will never come again. Capture or it is lost. In my experience, lost moments are also easily forgotten.

And to be honest, it was difficult to catch a really good photo of him. So many times he had a quizzical look because he didn’t think this moment was important enough for a photo, or he’d have a big smile at the start of a group photo then fade during subsequent takes because one shot should be enough and why are we still standing around here… or he’d just keep talking so his face fell into odd contortions. So perhaps a reason why his wife and I each took bunches of pictures of him later in life was the challenge of catching a good one.

When the family realized the patriarch was terminally ill, we dealt with the news in different ways. I coped by jumping into my digital image collection and searching through all pictures of him. Finding and collecting those solid reminders of past memories sustained me through the inevitable decline. Next I turned to my mother-in-law’s camera phone, where she had followed him through his mundane habits. A morning of dividing day-lilies, a lunch with his signature whole-grain bread, an afternoon puzzling through bills. Candid images to avoid his dismissive ‘what are you doing’ frown.

I can’t thank her enough for those pictures.

The highlights went into a slideshow of my father-in-law’s life which looped silently through the reception after his memorial service. Almost 250 photos told his very interesting life story. The photos in exotic locales were impressive, but the photos in familiar places doing familiar tasks were endearing.

Why shouldn’t we celebrate the tiny moments? And when those moments are gone, let’s enjoy the memories of what was. Not to dwell too much on them or futilely wish we could go back, but to smile at the memories and make connections to today.

Here’s to the photographers, the chroniclers, the memory-keepers. Capture the little things so we may hold them dear.